This is part five of a multi-part blog, sharing my thoughts on the book Good to Great by Jim Collins. Here are links to Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and Part 5. In this update I’ll be covering chapters 7 and 8 from the book.

Chapter 7 – Technology Accelerators

Much of this chapter talks about how everyone in business (and society at large) is caught up on technology and fears that if they don’t keep on top of it they’ll be left behind. However according to their study, technology was not that significant:

“We were quite surprised to find that fully 80 percent of the good-to-great executives we interviewed didn’t even mention technology as one of the top five factors in the transition. Furthermore, in the cases where they did mention technology, it had a median ranking of fourth, with only two executives out of eighty-four interviewed ranking it number one.”

Considering how important technology was to some companies this may be surprising, but most CEOs focused on other parts of their company – either their people, their culture, their organization, etc. The author then sums it up well in two sentences: “Like the Daytona 500, the primary variable in winning is not the car, but the driver and his team. Not that the car is unimportant, but it is secondary. Mediocrity results first and foremost from management failure, not technological failure.”

They also gave an interesting non-business example: Vietnam. The US was technologically superior, but technology alone wasn’t enough to win the war. We could spend days talking about businesses who thought some technology was going to be their ticket to untold millions, only to fail miserably.

In short, the question goes back to your company’s Hedgehog Concept. Your Hedgehog Concept may not have anything to do with technology once you really get to the heart of it. It may be that technology is simply being used to leverage your approach toward your Hedgehog Concept. The book shares a great example of this with Walgreens.

Walgreens decided they were in the business of being a convenience store. They got rid of their lunch counters and moved stores from the middle of the block to the intersections in order to increase traffic flow (even if the move cost them millions of dollars up front). Most importantly, Walgreens came up with a system to connect all their pharmacies so customers could pick up prescriptions at any Walgreens location, nationwide.

The technology required to connect all their pharmacies was a game-changing event. There was no other company in the world that had anything like it at the time. But the technology was being driven BY their Hedgehog Concept – not the other way around. Their aim was to be the best convenience store possible, not to revolutionize technology.

I particularly liked this passage from the book: “This brings us to the central point of this chapter. When used right, technology becomes an accelerator of momentum, not a creator of it. The good-to-great companies never began their transitions with pioneering technology, for the simple reason that you cannot make good use of technology until you know which technologies are relevant.”

Again, this reminds me of celebrity CEOs who had grand visions of technical revolutions that didn’t pan out. Heck, it’s even true of the ones that do pan out. A quick Google search will find thousands of articles discussing how iPod and iTunes aren’t revolutionary technology, and how the key to Apple‘s success has been their marketing (Link 1, Link 2, Link 3). That makes sense, when you think about it. I don’t know what Apple’s Hedgehog Concept is, but I’d be willing to bet it’s centered strongly on how their customers feel when using Apple products – and that’s tied much more closely to marketing than it is to MP3 technology.

Again, the technology was used to leverage what was in the Hedgehog Concept, not the other way around. Once you know what you’re trying to achieve then it’s much easier to look towards technology and ask, “Which technologies will help us reach our goal?” If you don’t need a certain technology (or you don’t need it to be cutting edge to get the job done) that relieves a lot of tension and fear of being left behind. Who cares about being left behind if that’s not the direction you want to go in the first place?

Chapter 8 – The Flywheel and the Doom Loop

Think of a fully loaded eighteen-wheeler – once it’s up to 60mph it’s really hard to stop suddenly. Now imagine the weight of a fully-loaded eighteen-wheeler going 60mph compressed into a circle six feet around. That’s a flywheel. A flywheel is a way to store that energy in one place, instead of having it driving down the street. When it’s stored in one place you can take a little out, or put a little in as needed without too much effort. Meanwhile you have a whole lot of energy available if you need it.

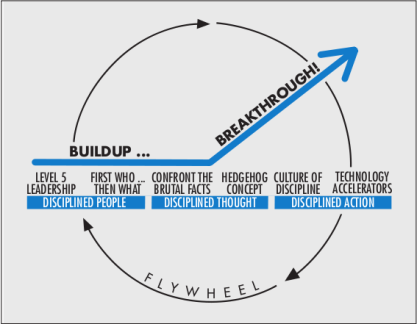

Getting the flywheel up to speed is like getting the semi up to speed: first you start off in low gear, moving very slow. As you pick up speed you change gears. Doing this multiple times you’ll eventually get up to great speeds. Good to Great companies come about by building up the same way. One step at a time, each decision, each action building on the one before.

Now imagine what it’s like to work at a place where you spend a week getting the flywheel up to speed spinning in one direction only for your boss to come in and stop the wheel. Then you’re told to spend the next week getting the wheel up to speed in the other direction. Again your boss comes in and stops the wheel, and tells you next week you’ll be getting the wheel spinning in the first direction again. This keeps momentum from building, and keeps a company from going anywhere. Even if each change of direction is accompanied by a kickoff party, media, and fanfare the effect is the same.

Good to Great companies have the discipline needed to get their flywheel up to speed, but it comes from having done all the steps discussed earlier in the book. When you get your Hedgehog Concept crystallized, that tells you which direction you need that flywheel to spin. When you get the right people into the right seats (and the wrong people off the bus) that gets everyone aligned to spin in the same direction. Once you get the flywheel spinning in the right direction you can look for technology that accelerates you.

Aside from internal pressures there are also external ones: customers and shareholders. The book only mentions shareholders, but I’d like to mention customers too. Customers can’t tell you what your Hedgehog Concept is. Only you can do that. As the old saying goes, if you try to please everyone the only thing you’ll succeed in doing is driving yourself crazy. The important thing is to dig deep and find your Hedgehog Concept. If you want to change from a hot dog stand to a taco stand, you’ll lose some customers and gain others.

The book tells the story of Gillette, who revolutionized the shaving industry when they introduced the Mach 3 with three razor blades. Before Gillette finalized the product and released it to the world they fought off a hostile takeover that was so enticing to shareholders that CEO Coleman Mockler and other officials in the company spent time personally calling the largest shareholders and basically saying, “We’ve been working on a secret project that’s going to increase Gillete’s stock price far above what these people are offering you. The project is nearly complete, just hold out until next year and you won’t regret it.”

Shareholders can be a source of pressure too, but the important thing to remember is that shareholders were a pressure to both Good to Great companies as well as companies who didn’t make it. Again, it goes back to having the discipline to hold your course. The book gives a number of examples supporting this that I don’t have space to go into – feel free to buy the book or check your local library if you’d like to read more on that.

A Word About the Misguided Use of Acquisitions

This book also gives example after example of companies that made acquisitions that put the company belly up. Growing for the sake of growth itself will lead to failure. Making an acquisition as a way to spark new growth or motivate people leads to failure. The CEO may increase the value of the company in the short-term, cash out, and be gone in 3-5 years, but then the deck of cards will fall when everyone realizes the acquisition was a bad decision. Hold off on making acquisitions until after you have your Hedgehog Concept figured out, and make choices based on how it strengthens your core goals. Your chances of success will be much improved.

That wraps up Chapters 7 and 8. Next week I’ll post the last installment of this series, covering the last chapter in the book.