I like to read … a lot. I tend to like articles over books, but I do have a few books I’ve wanted to read for a while now. And when I do read books, I like to take notes. Today it occurred to me that I could post my notes here on my blog. Maybe they’ll be of use to someone who otherwise wouldn’t have read the book, or maybe did read it but would like to hear someone else’s view on the material.

The first book I’ll post my notes on is Good to Great, by Jim Collins. The book was published in 2001 after a very long, intensive study of multiple large corporations. IIRC, the study took over a year, maybe over two years. Mr. Collins’ researchers grouped the companies into three categories:

- Companies that roughly followed the performance of the general stock market

- Companies that far exceeded the performance of the stock market, but were unable to sustain that level of performance

- Companies that far exceeded the performance of the stock market, and sustained that level of performance for at least 15 years

The book (and my notes) uses the phrase “unsustained comparison companies” to refer to that second group of companies. These unsustained companies distinguish really great companies from temporarily great companies – after all, if you want to be great you want to know how to make it a lasting greatness. More importantly, comparing the sustained and unsustained companies does a great job of highlighting ideas that appear to be beneficial on the surface, but in the long run are not.

There were a few places that Mr. Collins used more than one example to highlight his topics, which made the book a bit wordy, but overall the book was so good that many times I copied entire sections of it into my notes, verbatim. I wound up with 23 pages of notes because of that, but obviously I won’t be posting all of it here. I do have enough for a series of posts though, so make sure to come back for more posts later.

Okay. On to Mr. Collins’ book. I have to say: I loved this book. Often I’ve worked for companies where I’ve instinctively known there were problems, and talked with my coworkers about the problems. Sometimes we were just stabbing in the dark, guessing what the source of the problem might be. Reading Good To Great was like turning on a light and putting my finger on precisely what the issue was. I was finally able to say, “Yes! That was exactly it!” That’s why this book was a best-seller – it gave people the vocabulary they needed to get to the heart of their problems. Once you see a problem clearly you have a much better chance of fixing it.

The book has 9 chapters. The first is an introduction, and chapter 9 compares the ideas from chapters 2-8 to topics in Mr. Collins’ earlier book, Built To Last. I’m going to use material from Chapters 1 and 2 for this post.

Mr. Collins and his team of researchers did an exhaustive study – the end of the book had 100 pages of technical data backing up their findings. In the process of sorting the data they came across a number of findings that very much went against what most people thought of as true:

- 10 out of 11 good-to-great CEOs were promoted from within. Comparison companies tried outside CEOs 6x more often.

- No systematic pattern tying executive compensation to performance. “The idea that the structure of executive compensation is a key driver in corporate performance is simply not supported by the data.”

- Both sets of companies had well-defined long term strategies. There’s no evidence that good-to-great companies had spent more time on their plans.

- The good to great companies did not focus principally on what to DO to become great; the focused on what NOT to do, and what to STOP doing.

- Technology cannot cause a transformation, but it can be an accelerator once you’re heading in the right direction.

- Mergers and acquisitions play no role in determining good-to-great companies.

- The good-to-great companies paid scant attention to managing change, motivating people, or creating alignment. Under the right conditions the problems of commitment, alignment, motivation, and change largely melt away.

- They produced a revolutionary change in their companies often without even realizing it (until after it had happened) because the changes did not require a revolutionary process.

- No one went from good-to-great due to luck. Greatness is not a matter of circumstance; it is a matter of choice.

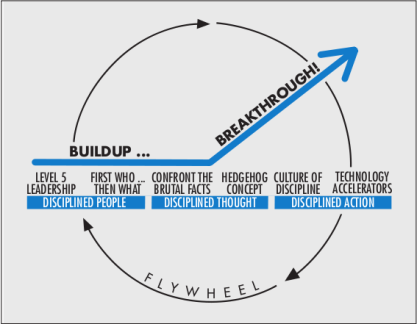

The other important thing introduced in Chapter 1 was this visual aid, which we’ll come back to again as we go over the material in the book:

So let’s jump right to Chapter 2: Level 5 Leadership. What is Level 5 Leadership? Here are some of my notes:

“Level 5 leaders channel their ego needs away from themselves and into the larger goal of building a great company. They have the will to do what must be done (even if it means firing a relative), but retain humility. Level 5 leaders set up their successors for success (lesser leaders set up successors for failure). Lesser leaders are I-centered, Level 5 leaders are we-centered.”

There’s always been a trend in management to downplay one’s ego and promote the work of your team but I think after this book came out it’s become something that managers have learned to do just to appear to be a Level 5 Leader. So how can we tell who’s seriously a Level 5 Leader? One phrase I liked from the book was, “Are you more of a show horse or a plow horse?” It’s good to toot your own horn now and then, but how much work are you doing, and how much tooting are you doing? (Pun intended.)

The author also provides a good metaphor called “The window and the mirror”: Good leaders look out the window to see what went right; they look in the mirror to see what went wrong. Bad leaders do the opposite – they look out the window to see what went wrong, and look in the mirror for what went right.

… which is very similar to that saying, “When you point your finger at someone else, you’re actually pointing three fingers at yourself.”

Another great point they made, and were able to back up with cold, hard numbers: “One of the most damaging trends in recent history is the tendency (especially by boards of directors) to select dazzling, celebrity leaders and to de-select potential Level 5 leaders.”

The book discusses this in more detail later, giving plenty of examples of “celebrity” leaders who come into the company with a lot of fanfare and made sweeping changes that appear to be very productive at first. Then either the leader’s efficiency wanes or they leave the company, and the company slides back to where they were before, or worse. And this is not just a “once in a blue moon” problem – going back to the table in Chapter 1: “10 out of 11 good-to-great CEOs were promoted from within. Comparison companies tried outside CEOs 6x more often.” I did the math on this, and let me put it into different words for you: If you hire a CEO from outside your company, you have a 55% chance of failing to sustain any improvements your company makes. Companies that promoted from within sustained their greatness 91% of the time.

The book also listed a table that tried to explain the Five Levels of Leadership. The distinction between Level 4 and Level 5 was that Level 4 Leaders tended to control the company through their own personal power (charisma, verbal and/or mental power, personal discipline, etc). On the nice end of the spectrum they were considered tenacious, visionaries who wouldn’t take no for an answer. On the not-so-nice end of the spectrum they were called tyrants, verbally abusive, etc.

By comparison, Level 5 Leaders were also tenacious, but they strove for excellence not for their own ego’s sake, but for the sake of the company. There’s an entire section later in the book about how the successful companies created a culture of discipline … meaning it was the culture of the whole corporation, not just the leader of the company. When you have the right people on the bus you don’t need to be a disciplinarian. When you have the right people they take care of things without being told to, and even better, the company will continue to do the right thing even after the Level 5 Leader retires or moves on. When a Level 4 Leader leaves a company it falls back to where it was, or worse.

The problem is that Level 4 Leaders tend to be a lot more celebrity-like than Level 5 Leaders, so when a Board of Executives interviews for a CEO position lately (or at least at the time the book was written) they’ve been picking Level 4 Leaders over Level 5 Leaders, which just causes problems down the road. But isn’t that exactly what we’ve been saying for the last 20 years? One of the problems with the world lately is that corporations seem to keep making short-sighted choices for immediate profit rather than being smart and thinking about the long-term benefits.

Well – that’s a lot of writing for one post. In a few days I’ll write up a post covering Chapter 3. Be sure to subscribe – subscribing is free – to be notified when I post more material. The box to add your email address is on the upper right side of this page. (Not to mention I’ll also be continuing to post notes on other books as I read them.) See you soon!

I’m curious about a few things posted between your opinion and examples stated in the books listed, namely the definition of improvement, whether there are common strategies among those hired-gun CEOs, and how to rectify focus on short-term goals over long-term goals.

First, I’d imagine improvement is defined as stock price, return on assets, or some similar metric. I don’t necessarily want to make an assumption, however.

Next, the fashionable course to short-term profitability seems to be the paring down of infrastructure, which in turn cuts down on expenses for the likely term of a CEO’s tenure. By the time the lack of support expertise, component quality, or any similar factor becomes an issue, the cause of the problem will likely be at his or her next stop executing a similar plan.

Finally, since the short-term focus is, in the present culture, so much more profitable to individual managers than the long-term focus, how would this be rectified. So much is made over the almost incomprehensibly large option packages handed out to executives, but the first company to completely eliminate those packages will be the first company to have trouble retaining that home-grown talent mentioned in your itemized list as so crucial to the long-term success of the company. Restructuring those option packages by extending the time required to either stay with the company or to hold onto the options before they’re exercised would likely have a similar, if lessened, impact.

Hi there. Thanks for reading, and for the comment. In a nutshell, the next chapter of the book is about “getting the right people on the bus, and the wrong people off.” The study found that when you have the right people on the bus everyone is much happier about being where they are, and pay becomes a smaller portion of the equation. So the answer to the question you asked is to sort of sidestep the payment question altogether and say, “We’re not going to pay you any different. We’re going to expect you to think long term, and that’s that. If you can’t do that or don’t want to, this isn’t the place for you.” One of the things I like about this book is that it’s nice to see that there are statistical proofs of things many people know and would consider “common sense.” You shouldn’t have to pay people extra to do this – it ought to be part of who they are intrinsically.

I thought the book was excellent, and pinpoints a number of the problems in corporations these days. Either bookmark this blog or subscribe for updates, I’ll be posting more of my notes every few days, and then I’ll continue posting notes from other books I’m reading.

Pingback: Good to Great (Part 2) | Trading On Up